Why is hunger making a comeback across the globe?

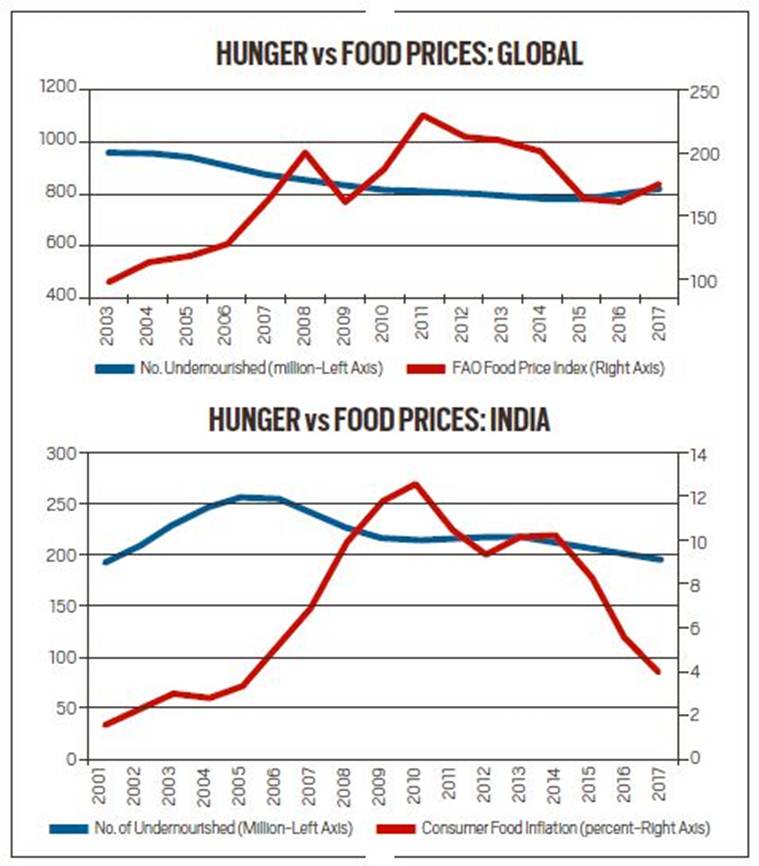

Global hunger numbers are on the rise again. After witnessing a decline both in relative and absolute terms for a decade from 2003 to 2014, global hunger numbers have seen a reversal in the last three years, according to a United Nations report. During the 2003-14 period, this number had fallen from 15.1% to 10.7% of total population corresponding to a decline in the number of undernourished people globally from 961.5 million to 783.7 million. But since 2014 the number has gone up from 10.7% to 10.9% of the global population rising in 2015 to 784.4 million, to 804.2 million in 2016 and touching 820.8 million in 2017.

These alarming numbers have been put forward by Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations which indicate that a growing number of people across the globe are not able to consume the minimum calories required to lead a normal, healthy life.

This is despite the world agricultural prices suffering a drastic fall since 2014. According to the FAO Food Price Index average of 201.8 (base year: 2002-2004=100) in 2014 slumped to 164 in 2015 and further declined to 161.5 the following year before partially recovering to 174.6 in 2017.

This is in complete contrast to the upwardly trend of the index witnessed between 2003 – when it was 97.7 – and 2011 when it jumped to 229.9 and constantly maintained a 200 plus level till 2014. But what is interesting is that throughout this period global hunger numbers kept going southwards even though food prices were on the rise.

India no exception

If we focus on India we find that this trend is more or less reflected in the numbers thrown up by the Indian economy too. During 2001 and 2005 the annual food inflation based on consumer price index for industrial workers was recorded between 1.6% and 3.4% during which time the number of undernourished people in India rose from 191.2 million to 256.5 million. What is interesting to note is that even though food inflation had hit double digits by 2009-10, in keeping with the global trends, yet the number of hungry in the country had come down to 214.4 million by 2010.

Numbers also indicate that even if food inflation remained in the double-digit till 2014, yet one did not see any corresponding increase in the number of undernourished people and this figure has actually dipped in the last three years –bucking the global trend. However, it is pertinent to point out that this reduction in the number of undernourished in India is not as sharp as the reduction in food inflation in India that was below 4% in 2017. (As explained in India chart).

This paradox has led to several theories as to why the collapse in global commodity prices and the drop in inflation since 2014 has not resulted in a reduction in hunger? Because common sense dictates that such a scenario should have led to food becoming more affordable.

Experts across the world including FAO Assistant Director General Kostas G Stamoulis who works from Rome attribute this paradox to three factors:

Conflict

Conflicts in many parts of the world (North and northern sub-Saharan Africa, (West Asia, Central America and Eastern Europe) have resulted in large-scale displacement of the civilian population leading to food insecurity. Conflicts – whether they be between armed groups or state-based have risen dramatically in number since 2010. These conflicts have given rise to a situation where approximately 500 million out of the 821 million of the undernourished live in conflict zones.

Climate change

Changing nature of rainfall, its duration and changes in the normal weather coupled with abnormal variations in temperature has led to catastrophic natural tragedies ranging from droughts to floods, storms, heat waves, etc. South Sudan has been hit by a famine for several months in 2017 and its recurrence cannot be ruled out.

Similarly, countries like India that are dependent on monsoon rains for their agriculture were hit hard by the El Nino effect in 2015-16. This phenomenon which results in — the formation of a band of warm ocean water in the equatorial eastern Pacific Ocean adversely impacts countries that are dependent on agriculture and or fishing. This was one of the strongest natural climatic events in the last 100 years which resulted in 2016 and 2015 being recorded as the warmest and the second warmest years in earth’s recorded history.

Agricultural areas across the world continued to suffer from temperature anomalies resulting in more frequent spells of extreme heat from 2011-16. In fact, the effect of climate change can be seen in the fact that six of the warmest years on earth have occurred since 2010.

But it should have had an adverse impact on the production of agricultural produce thereby driving commodity prices up but surprisingly this was the very period in which many agricultural commodities including palm oil, cotton, sugar, rice, wheat, corn, soyabean, milk etc had a bumper produce. This, in turn, led to a mismatch between demand and supply leading to farmers across the globe including in India getting less remuneration for their produce.

Economic slowdown

But the most important factor for hunger making a comeback globally despite bumper agricultural produce is the economic downturn the world witnessed during this very period. This led to lower prices for all types of commodities whether they be agri-produce, metals or oil. This in turn adversely affected revenues of those countries who were largely dependent on commodity exports. This resulted in lower government spending on welfare measures. The fact that most of the agri-producers themselves are poor and had to contend with lower wages or prices during this period led to an increase in the number of hungry people worldwide even as the world saw soaring agri-produce.

This theory is backed by the Director of and Production Technology Division at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington – Channing Arndt, who opines that experts need to find out why world hunger is again increasing or is not decreasing at the same rate as before as can be seen in countries like India.

This problem was foremost on the minds of economists, policymakers, nutrition experts and others, during a three-day global conference in Bangkok. The FAO-IFPRI ‘Accelerating the End of Hunger and Malnutrition,’ global conference was aimed at discussing on how to end the occurrence of undernourishment by 2030 under the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

While agreeing with Stamoulis’s explanation of economic slowdown, Arndt believes that a sharp increase in food prices like those witnessed in 2008-09 is bad for everyone in the short-term with the exception of net sellers. But he goes on to say that if prices continue to remain high over a long period then it may have beneficial effects on the economy. He states that such a situation could push production upwards leading to increased farm incomes. He says this could mean a jump in the demand for unskilled labour leading to a rise in overall rural wages but cautions that the urban poor could be adversely hit in such a scenario.

Arndt’s colleagues at IFPRI, William J Martin and Derek D Headey have used state of the art econometric tools and simulation models to explain how rural poor were benefitted by the increase in food prices in the last decade and how this could possibly have contributed to faster global poverty reduction starting from the mid-2000s. They have also show that how the recent slowdown in agri-produce could have a negative impact on poverty reduction across the globe. (annualreviews.org).

This leads us to an important question in the Indian scenario keeping in mind that consumer food inflation during the period of 2014-15 to 2017-18 averaged 4.6%, as opposed to 4.7% rise in the general CPI. Even in the current fiscal (from April to October), retail food inflation has averaged 1.8%, as against 4.2% for the overall CPI.

How much hunger and rural poverty will be reduced due to this interplay between CPI and food inflation is a question worth asking?